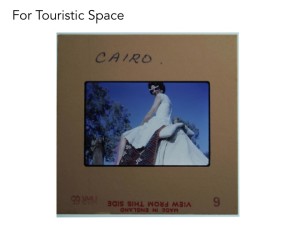

Somewhere in this image is my nana – Dot Dummett. This picture was taken in 1966 when she left Melbourne aboard the very first Women’s Weekly World tour cruise ship. Enticed by images of the world that she found in the pages of that venerable magazine – of coronations and castles and exotic locales – she made sure to book her place on the first Women’s Weekly World tour without hesitation. My grandfather, who had seen some parts of the world during his service in World War 2, had no intention of ever leaving Australia again and confined his interest in the world to his own backyard and the pages of the National Geographic.

I found this image while I was scouring old slides that I inherited from my grandfather Fred after he passed away in 2010. What immediately struck me about the image was not the sight of my grandmother riding a camel – though that is quite a striking element in this image. Rather, it was the manner in which she was dressed. A white dress. On a camel. In Egypt in 1966. What was she thinking?

I found this image while I was scouring old slides that I inherited from my grandfather Fred after he passed away in 2010. What immediately struck me about the image was not the sight of my grandmother riding a camel – though that is quite a striking element in this image. Rather, it was the manner in which she was dressed. A white dress. On a camel. In Egypt in 1966. What was she thinking?

Clearly she had no intention of getting dirty, in a physical sense and a metaphoric sense. She would remain as untouched by her experience as she could possibly manage. She was a true colonial’s colonial whose interest in the geopolitical extended only to the naming of royal children and the live telecast of the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo.

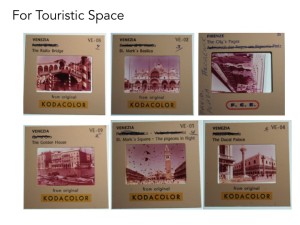

What is also striking about this image is its rarity amongst her collection of slides of her travels. The fact that she is in the image is its first marker as a rare image. The second marker is that it is a snapshot. She did not, in fact, take most of the images she returned home with. Her collection of holiday snaps was predominantly made up of images, in the form of slides, taken by professional photographers.

Again, what is striking about these images is not the images themselves but rather her desire to erase any marker of difference, which might challenge her to see these scenes through other (read ‘foreign’) eyes. Hence, she has scratched out the Italian renditions of the names of these ‘sites’, leaving only the more familiar (and one might argue, in her terms, ‘correct’) English names for them.

It might be tempting to argue that my grandmother’s travel experiences were indicative of tourism at a particular time and place in history. But I think that would be wrong for a number of reasons.

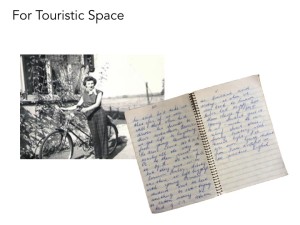

Firstly, I also have my aunt’s diaries from the mid 1950s where she details her travels hitchhiking around Europe with her girlfriends where she muses about this or that lift they have been given and the Iranian student that she tutored in a youth hostel.

Firstly, I also have my aunt’s diaries from the mid 1950s where she details her travels hitchhiking around Europe with her girlfriends where she muses about this or that lift they have been given and the Iranian student that she tutored in a youth hostel.

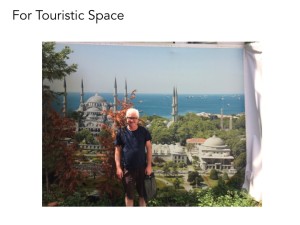

Secondly, there are no shortage of tourism experiences on offer now that continue to promise the kind of perfect (and therefore at once removed) experience my nan was seeking.

I think the difference lies in the ways in which space is both conceptualised and produced in and by the different practices and discourses of travel and tourism. And I’m interested in the ways in which this plays out in photographic practices which in turn has implications for the ways in which we conceptualise space and politics and our being-together in the world.

Visitors to the website Googlesightseeing.com are immediately confronted with a question of disarming profundity when they land on the opening screen: Why bother seeing the world for real? The question suggests that there is in fact a ‘real space’ outside of the space of the screen that has been captured and brought to the viewer, in this case through satellite images and grabs from Google Earth and Streetview. These spaces are represented in and by the images that are the main feature of the site. It also implies that ‘seeing the world’ is merely a matter of vision. This way of framing tourism – as sight/site seeing – used commonly in a range of modes and expressions of armchair travel (or the ‘tourism of immobility’), not only undercuts the potentially transformative effects of actual travel experiences by reinforcing an imagination of space as representation, stasis and closure, it also resists an understanding of space (and consequently history and politics) as open, unfolding, becoming and event.

Visitors to the website Googlesightseeing.com are immediately confronted with a question of disarming profundity when they land on the opening screen: Why bother seeing the world for real? The question suggests that there is in fact a ‘real space’ outside of the space of the screen that has been captured and brought to the viewer, in this case through satellite images and grabs from Google Earth and Streetview. These spaces are represented in and by the images that are the main feature of the site. It also implies that ‘seeing the world’ is merely a matter of vision. This way of framing tourism – as sight/site seeing – used commonly in a range of modes and expressions of armchair travel (or the ‘tourism of immobility’), not only undercuts the potentially transformative effects of actual travel experiences by reinforcing an imagination of space as representation, stasis and closure, it also resists an understanding of space (and consequently history and politics) as open, unfolding, becoming and event.

This argument follows on and draws inspiration from geographer Doreen Massey’s articulation ‘of a new conception of space’s potentially disruptive characteristics: precisely its juxtaposition, its happenstance arrangement-in-relation-to-each-other, of previously unconnected narratives/temporalities, its openness and its condition of always being made’ (Massey, 2005: 9). So one might argue that thinking of space as more than simply there but as a product of social relations, as a sphere of a multiplicity of trajectories, allows you to not only experience touristic space as transformative but reinvigorates touristic space as a space of the political. Tourists do not just travel across space to reach a destination, a place, that waits patiently for them to arrive, take their snapshots, and then leave (leaving the place much as they found it). Whether they are aware of it or not, they are a ‘part of the constant process of the making and breaking of links that is an element in the constitution of themselves (ourselves), where they (we) are not, where they (we) are going and thus space itself’ (Massey, 2005: 118). Media representations of travel and tourism work to create touristic spaces while also being a by-product of tourism.

This argument follows on and draws inspiration from geographer Doreen Massey’s articulation ‘of a new conception of space’s potentially disruptive characteristics: precisely its juxtaposition, its happenstance arrangement-in-relation-to-each-other, of previously unconnected narratives/temporalities, its openness and its condition of always being made’ (Massey, 2005: 9). So one might argue that thinking of space as more than simply there but as a product of social relations, as a sphere of a multiplicity of trajectories, allows you to not only experience touristic space as transformative but reinvigorates touristic space as a space of the political. Tourists do not just travel across space to reach a destination, a place, that waits patiently for them to arrive, take their snapshots, and then leave (leaving the place much as they found it). Whether they are aware of it or not, they are a ‘part of the constant process of the making and breaking of links that is an element in the constitution of themselves (ourselves), where they (we) are not, where they (we) are going and thus space itself’ (Massey, 2005: 118). Media representations of travel and tourism work to create touristic spaces while also being a by-product of tourism.

As Massey argues, ‘[c]onceiving of space as a static slice through time, as representation, as a closed system are all ways of taming it. They enable us to ignore its real import: the coeval multiplicity of other trajectories and the necessary outwardlookingness of a spatialised subjectivity…if time is to be open to a future of the new then space cannot be equated with the closures and horizontalities of representation. More generally, if time is to be open then space must be open too. Conceptualising space as open, multiple and relational, unfinished and always becoming, is a prerequisite for history to be open and thus a prerequisite, too, for the possibility of politics.’ (59)

I’d like to tease these ideas a little, and these observations are, I should add, preliminary and part of a larger project on tourism, neoliberal discourses and space that I am currently pursuing that began when I first visited Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city, in 2011.

Istanbul is becoming an increasingly important space in the development of tourism in Turkey; it is consistently outpacing the sector’s general growth which is still substantial – Total visitor numbers to Turkey rose from 16.302 million in 2003 to 36.776 million in 2012. While the number of visitors to Ä°stanbul was 3.151 million in 2003, this number hit 9.281 million in 2012.

Alongside this growth in tourism is a massive commitment to unbridled ‘development’ by the Erdogan government. Internal resistance against this was most recently seen in the protests to stop Gezi Park near Taksim Square being turned into a shopping mall and hotel precinct. The response from the Turkish authorities was swift, deadly and well documented. There are ongoing protests against a proposed third bridge across the Bospherus in a part of the city which contains the forests, the ecological reserves, water reserves and water basins of the city. There are also protests against the building of what Erdogan has claimed will be the world’s largest airport on an area of 7,659 hectares in the same area. Some 6,172 hectares of this area is forested land, raising anger among environmentalists about the ecological footprint of the project. More generally, Istanbul is also undergoing the transformation from an industrial city to a finance and service-centered city, competing with other world cities for investment. This means that the working class who actually built the city as an industrial center no longer have a place in the new consumption-centered finance and service city. This can be clearly seen in this documentary

Alongside this growth in tourism is a massive commitment to unbridled ‘development’ by the Erdogan government. Internal resistance against this was most recently seen in the protests to stop Gezi Park near Taksim Square being turned into a shopping mall and hotel precinct. The response from the Turkish authorities was swift, deadly and well documented. There are ongoing protests against a proposed third bridge across the Bospherus in a part of the city which contains the forests, the ecological reserves, water reserves and water basins of the city. There are also protests against the building of what Erdogan has claimed will be the world’s largest airport on an area of 7,659 hectares in the same area. Some 6,172 hectares of this area is forested land, raising anger among environmentalists about the ecological footprint of the project. More generally, Istanbul is also undergoing the transformation from an industrial city to a finance and service-centered city, competing with other world cities for investment. This means that the working class who actually built the city as an industrial center no longer have a place in the new consumption-centered finance and service city. This can be clearly seen in this documentary

So while these Istanbul spaces are highly contested and politicised, the function of tourist representations of Istanbul, that are created both by and through tourism, empty space out – turning it into a series of ‘time-slices’ that reinforce the idea of space as merely there, eternal, uncontested and depoliticised.

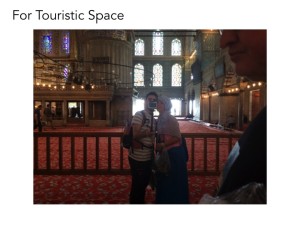

The average length of stay for a visitor to Istanbul is 2.3 days (Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2007). Tourism activities are heavily focused on two main areas – Sultanamhet and Taksim/Beyolglu.  Like many other tourists, my first on the ground experience of Istanbul was premediated by images such as these: show Hagia Sophia, Blue Mosque, Galata Tower, Topkapi Palace.

Like many other tourists, my first on the ground experience of Istanbul was premediated by images such as these: show Hagia Sophia, Blue Mosque, Galata Tower, Topkapi Palace.

There’s no doubt that these monuments are historically significant and aesthetically amazing. However, whatever auratic qualities they may have are very quickly displaced when you visit them by a sense that you are a part of a massive neoliberal tourism machine. The lines of tour buses that stretch along the roadside between the Blue Mosque and the Hagia Sophia disgorge an endless stream of people and come marked with signs that say things like “The Blue Mosque, The Hagia Sophia and time to yourselfâ€.

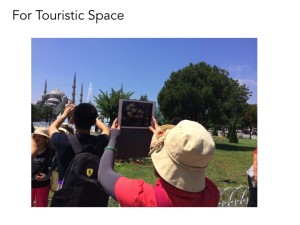

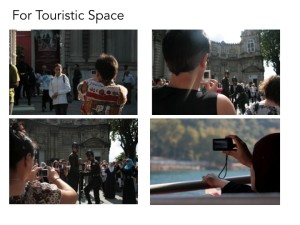

What I found most intriguing, however, was the sheer number of screens remediating these premediated images.

I’m not interested in this from the point of view of say Dean McCannell’s concept of staged authenticity (though of course there are interesting trajectories that this might take us on despite the reservations one might have about authenticity in general) or John Urry’s tourist ‘gaze’ – for Urry, the place still precedes the gaze and therefore, for me, works against a reading of space as event – always and ever open and constantly in the process of being made.

What the replication of the representations of these spaces does is work with the monuments themselves to create an illusion of fixity (which in turn reinforces and reifies the historical over the political) in spite of the fact that the monuments themselves show us the marks of time passing and space being constantly remade.  These steps from the Hagia Sophia are a startling example of this. Every footstep, every body is in the process of transforming the space even while those same bodies are attempting to capture its enduring thingness in images.

These steps from the Hagia Sophia are a startling example of this. Every footstep, every body is in the process of transforming the space even while those same bodies are attempting to capture its enduring thingness in images.

To return to Massey with some remixing: Tourists do not just travel across space to reach a destination, a place, that waits patiently for them to arrive, take their snapshots, and then leave (leaving the place much as they found it). Whether they are aware of it or not, they are a ‘part of the constant process of the making and breaking of links that is an element in the constitution of themselves (ourselves), where they (we) are not, where they (we) are going and thus space itself’ (Massey, 2005: 118).

Even more than this, the event of space-time exceeds any romanticised notion of the eternal essence of place-ness by also reminding us that ‘the hills are rising, the landscape is being eroded and deposited, the climate is shifting, the very rocks themselves continue to move on.’ (141) Because we can’t represent that in images doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

I tried to capture this sense in this collection of images taken on our most recent trip to Istanbul. It falls short of the mark. I’m not sure yet how one might or could represent such a set of ideas in practice but that is the thrust of the research I am undertaking with this ongoing project.

Inspired in part by the work of Massey and film maker  but also by the Greek philosopher Solon. Solon was a practitioner of the Greek institution of the theoria. Theoria, or θεωÏία in Greek, is the root of both the word theory and of tourism. Interestingly, the word translates to English as “to consider, speculate, or look at.†The theoria was a group of trustworthy people or an individual, theoros (θεωÏός), literally “spectator,†who would be dispatched to distant lands by the community, in search of the truth. The theoria’s job was to go to these faraway places, investigate, and report back to the community.